SUGOROKU

FROM SHOGUN TO GODZILLA,

A GRAPHIC GAMEBOARD HISTORY

OF MODERN JAPAN

Since the 15th century there have been hundreds of games with painted or printed boards that portrayed historical events, aspirations, and mores of society based on actual incidents during specific eras. One of the oldest, common in its many variations to all the countries of Europe and also China and Japan due to an unrecorded, early, transmission or some kind of cultural synchronicity, has been called many things but is generally known as, “The Game of the Goose.”

The prototype for many of the commercial European and American board games to follow, the goose game is typically a spiraling or circular path that one follows based upon successive rolls of dice. Snakes and Ladders, a 19th century English game with ancient, Indian, tantric, roots, and Chutes and Ladders, its American counterpart marketed by Milton Bradley, are similar, but have ladder-like grids to climb rather than roads to travel. Since games are always competitions to win or lose, life lessons, sports, business, politics, and warfare, have all been common themes. Almost every board game ever published has been of either the goose or snake model, including Candyland, Life, and Monopoly.

Sugoroku, which translates literally to “double six”, as in a pair of dice, refers to two different Japanese games – ban-sugoroku, which is almost identical to western backgammon, and e-sugoroku, or picture sugoroku, a sort of goose and snake combo that predates European examples by hundreds of years, migrated from China to Japan as early as the 13th century, and still exists there in paper and digital forms today.

In the mid-18th century, with the spread of ukiyo-e, Japan’s revered art of wood-block print-making, genre pictures appeared that were inexpensive enough to be purchased by the common classes. The popularity of picture sugoroku increased concurrently as the Japanese began embracing the games as New Year’s entertainments for children. The themes of these often beautifully graphic paper games were typically incidents from the literary and historical past, theater, and travel and touristic sights.

In the early days the games were made up of several small wood-block prints attached together to appear as one over-sized, sheet. With the advent of lithography in the 19th century e-sugoroku began appearing as single, large, prints as well. And because the Japanese print market was so extensive and competitive, sugoroku were ultimately created about every aspect of Japanese society, including history and war, women’s and girl’s themes including fashion and flower arranging, sports, education, adventure and exploration, nursery and folk tales, humor, moral lessons, advertising, and politics. Journalistic reportage of current events and almost every significant incident and social movement from mid-19th to mid-20th century Japan wound up on sugoroku, many of which were published and disseminated as inclusions in mainstream sources of print news - newspapers, magazines and publications for children. For this reason, except for a few intermittent gaps in the continuum, it is possible to tell the story of modern Japan from the 1860’s until post WWII, by studying the content of picture sugoroku, a largely unexplored, but deep and fertile repository of history.

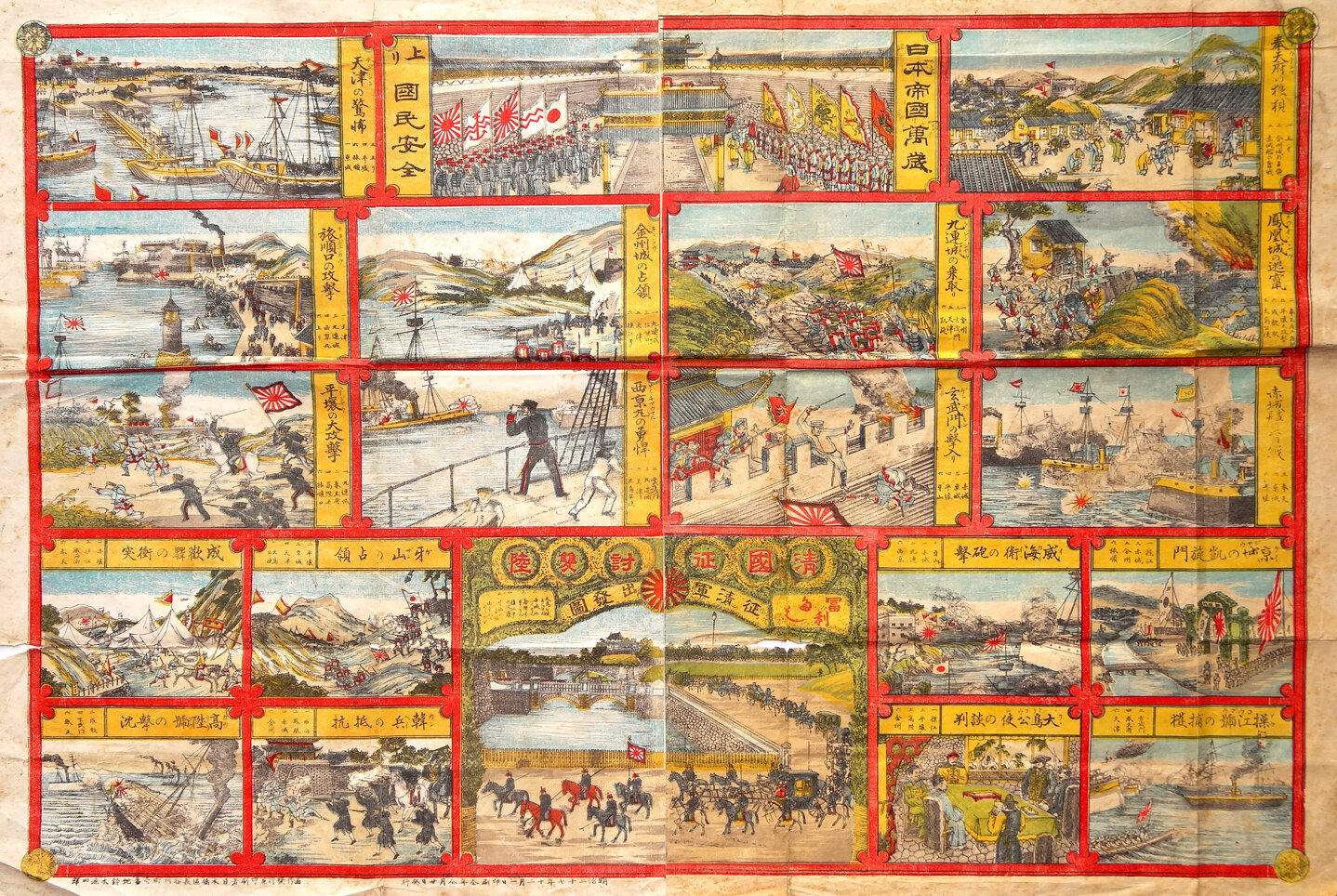

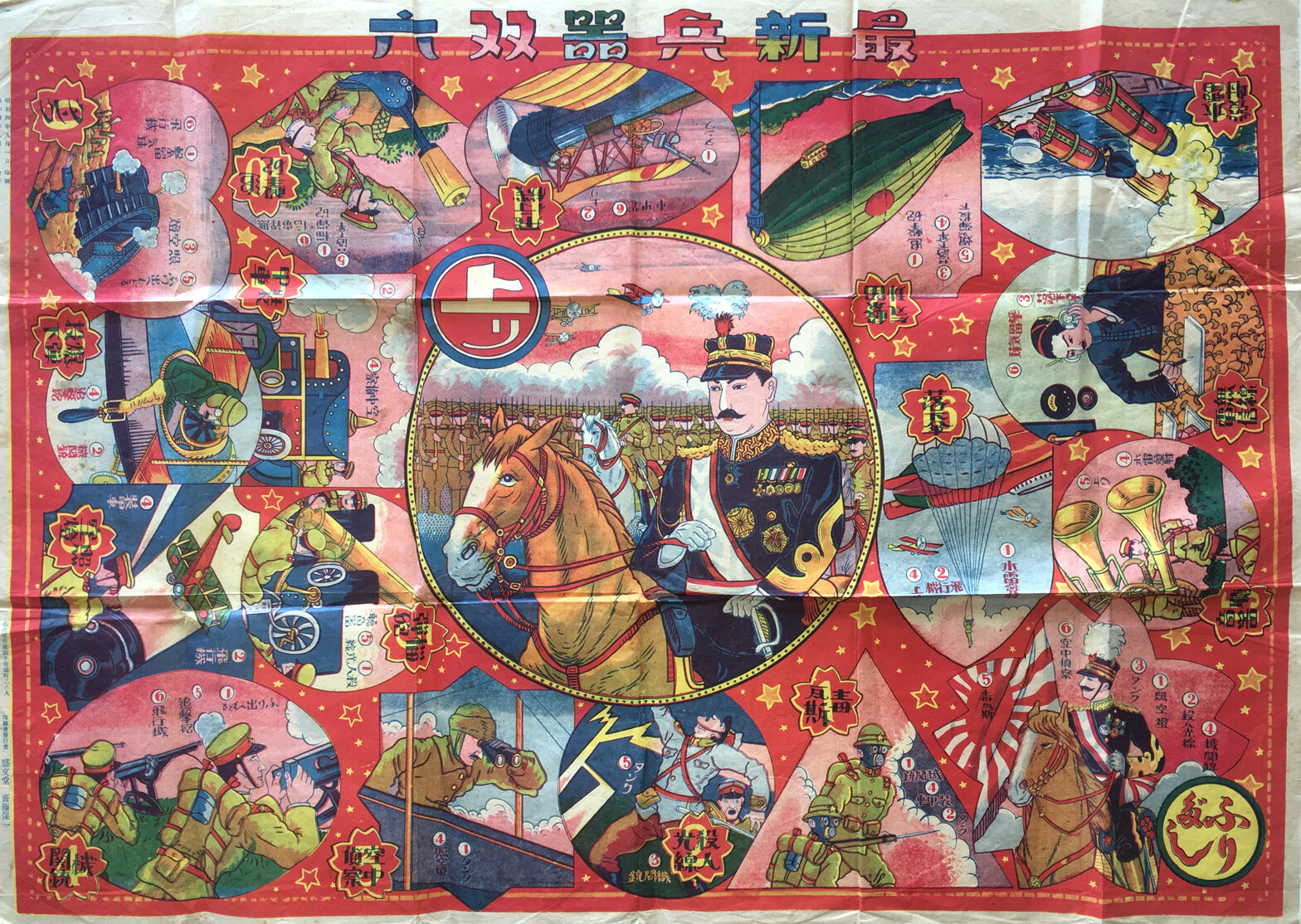

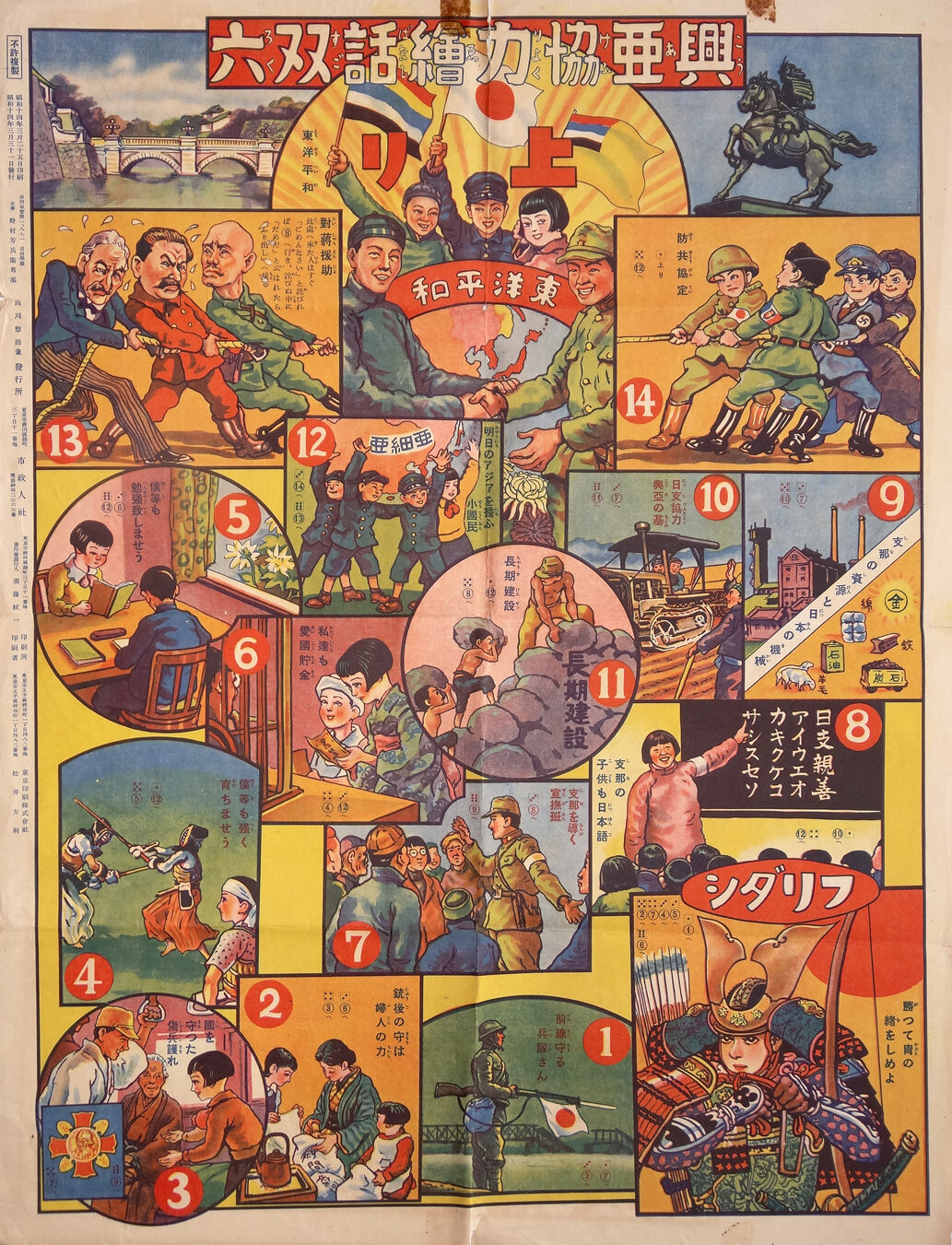

In concert with the nationalistic militarism sanctioned by the Japanese government, many e-sugoroku published during the tumult of Japan’s transformation toward modernity were archly propagandistic and showed actual battles, real aircraft, battleships, and weaponry, and accurate troop maps of the several Japanese colonialist incursions into the Asian mainland. The First Sino-Japanese War of 1895, the Russo-Japanese War of 1904/5, World War I, which Japan fought allied with the French and English, and the Second China War that began in 1931 with the Japanese occupation of Manchuria and ended at Nagasaki, were among the most popular sugoroku subjects. And after Pearl Harbor, when Japan’s Pacific overtures segued directly into World War II, picture sugoroku in support of the military that included death wishes to the Americans and British appeared as well, cheered on in almost every example, by flag-waving children.

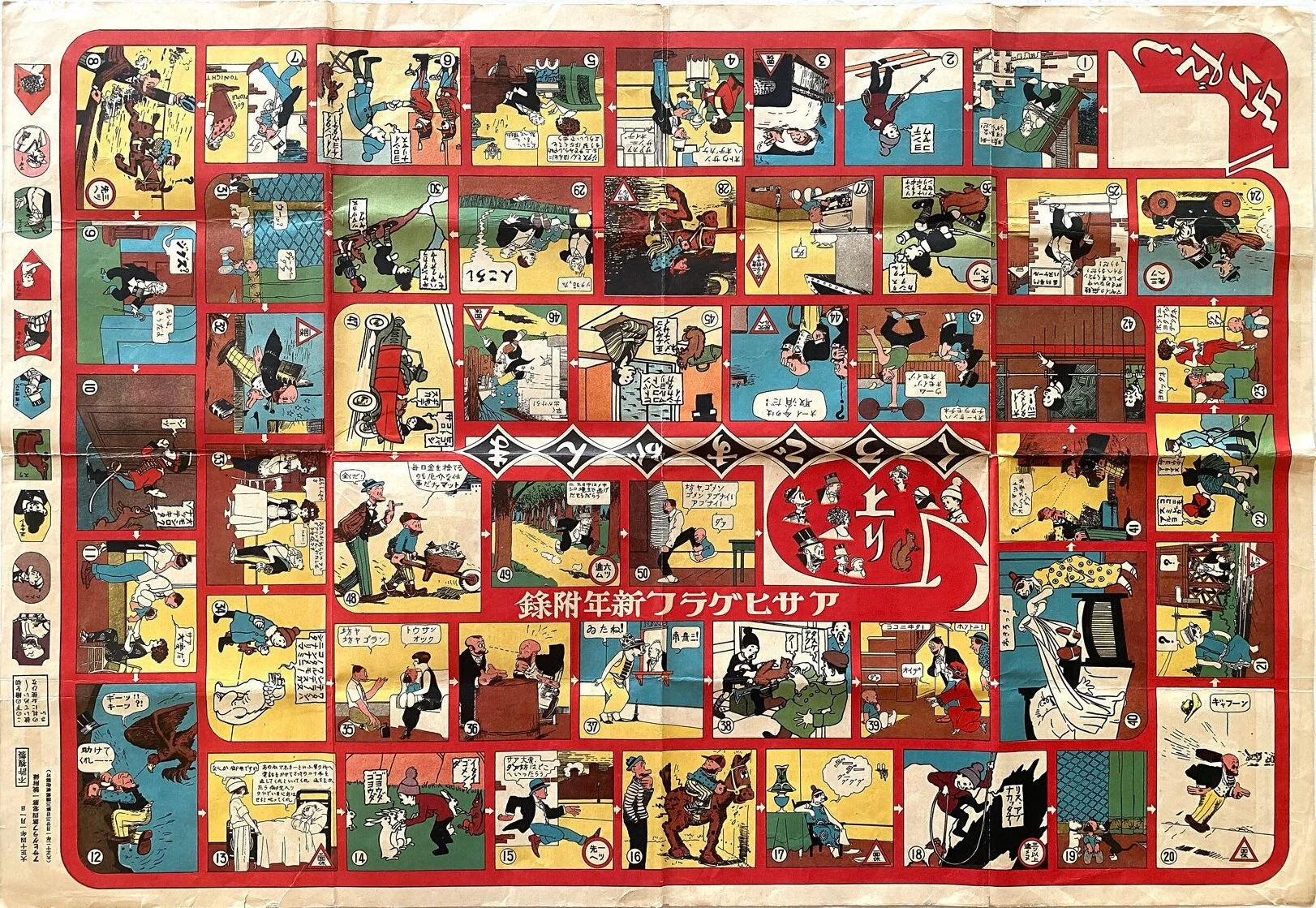

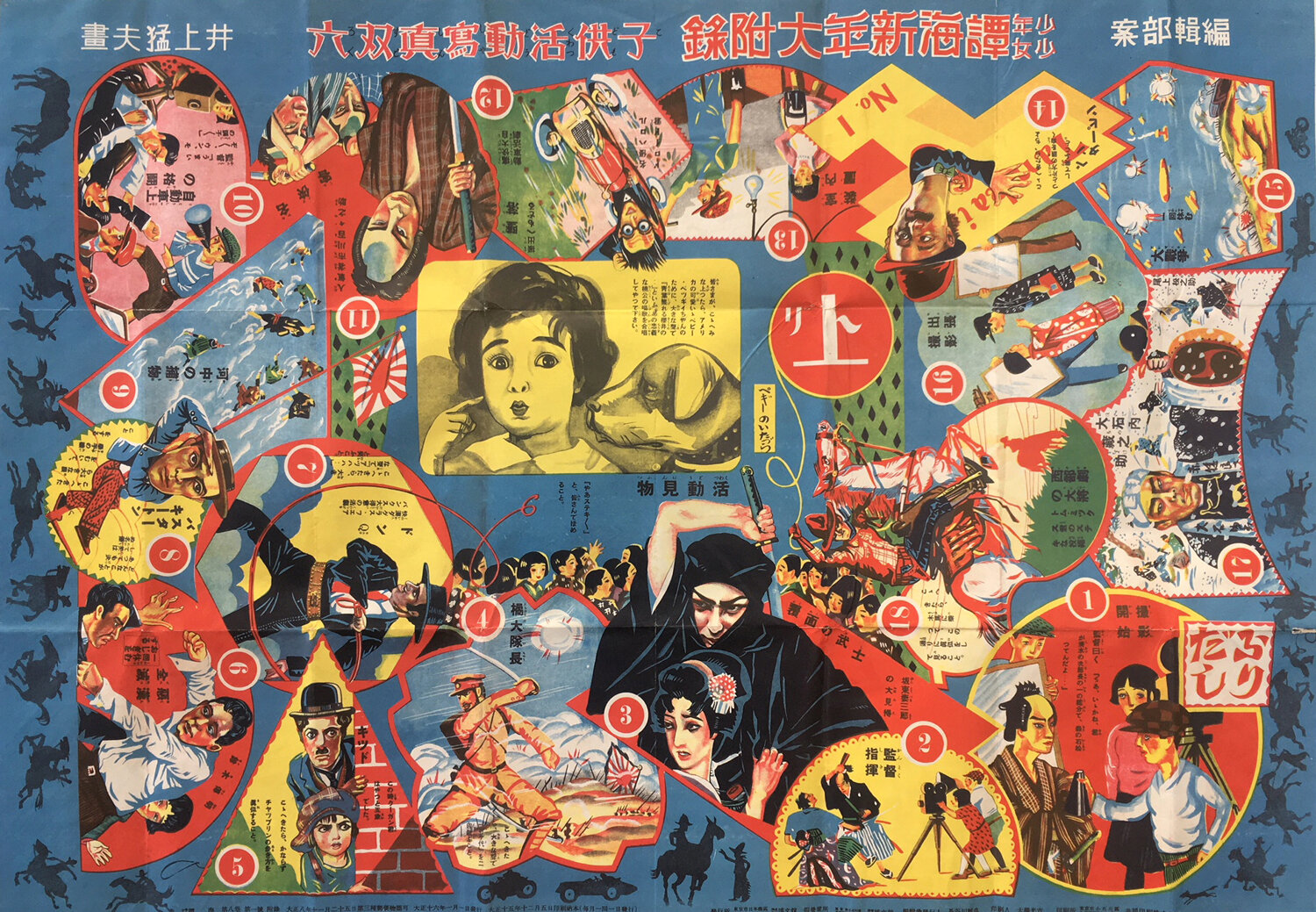

Of course Japanese life and culture after Commodore Perry landed in 1853 had more to offer than unending war and the sugoroku published in tandem with the militaristic kind included many benign and uplifting portrayals of modernity. From 1868 on, many forward-thinking Japanese began to embrace Western fashion, education, government, theater, transportation, and technology, and evidence of all of these appear in sugoroku. Kimono never went out of style and are still popular with Japanese women. But by the 1920’s, flapper dresses and bobbed hair, movies, subway maps, science fiction, the Olympics and western sports like skiing and baseball all became common sugoroku themes.

Many of the greatest ukiyo-e artists tried their hands at sugoroku while a broad palette of more modern graphic strategies, including realism, caricature, manga, silhouetting, montage, cartography, and the blending of black and white photos with colored illustration, all found their way into later games. Many 20th century sugoroku were designed and drawn by artists who were cognizant of international art movements like Art Nouveau, and many games created in the 1920’s and 30’s have the jazzy sophistication of Art Deco. Every sugoroku is a poster dense with information — a complex print designed as a game board but one embodying art, history, and propaganda, as well as aspiration and deceit.

The earliest sugoroku most often portrayed myths, incidents from Japanese literature and theater, and trips around Japan and the Tokaido Road. The vast majority of modern era sugoroku published were real children’s games - nursery rhymes, trips to the zoo, voyages with pets, etc. Focusing on what made Japan truly modern, I searched for current events, politics, technology, futurity, and conflict. Shown here is approximately 20% of my collection.

Norman Brosterman

Please click on image thumbnails to see the entire artworks and hover over each for more information. On mobile devices, a white dot appears in the bottom right of the “lightbox”. Tap the dot to show the caption.